For the spiritual aspirant to find balance in this world is a great art. Everyone who inhabits a body by necessity has to live in this world. It is an interesting paradox that many who renounce this world and become swamis, monks or priests can end up running large spiritual institutions, with more organizational responsibilities than an ordinary householder would ever have. You cannot escape this world, even if your only possessions consist of a begging bowl and a water pot.

The art of attaining balance has to be found within; so that even if you are king Janaka with incredible wealth and power, surrounded by all the beauty in this world you could let it all go up in smoke if God has you otherwise occupied with doing His work. It is impossible to know by lifestyle who has attachments—a person with very little in this world may be more attached to what they have than one who has remarkable wealth and possessions.

My mother-in-law spoke a few times about a family that was torn apart after the death of the adult-children’s parents. She said that some did not talk to each other after that, even though the things they were arguing about “was just junk.” I knew someone who said goodbye to a long-term friendship after a dispute over a cheap lawn chair. Attachment can bind us to the most inconsequential things.

Yoga means to yoke ourselves to God, not this world. Yet, we are expected to be good stewards of what God has given us. At one time in her life the only thing Carla had of value was a not-so-fancy car, but she made sure that she washed and vacuumed it so that it always looked its best. We work to find that balance so that we take good care of the things we are given, whether it be a few humble things, the responsibilities of a job or profession, or the ownership of a large company with many employees.

And with mindfully caring for things you have been given, you work to bind yourself to God-consciousness, making that your primary relationship in life. In doing so you can expect to have freedom from anxiousness, to feel peace in the midst of activity, you will intuitively know that the decisions you make are for the higher good of all, and you will fulfill the purpose for which you have taken incarnation.

To practice detachment, you can think about “what ifs.” What if God directed you to walk out your door and leave your home behind? What if He took away cars, furniture, bank accounts? Obviously you would need a place to live, food to eat, clothes to cover you, but what if He took away all that you now have? If you are like me you may have some sense of relief, “Now that responsibility is gone.”

I love the home God has given us, the vehicles, furniture and all the rest of it. I have great gratitude for Carla’s and my parents for gifting us with these wonderful things; that we can do the masters’ work here and share it with all of you brings about its most significant meaning to me. When I think back to the time when God asked me to enter into this journey without the ‘safety net’ of a paying job it was quite a mystery to me how God would provide. I had no fear that He would, only how would He do it? And do it He has, with great aplomb!

But just as He has given, so will He take away; even at the moment of death, the great equalizer, when all that any one of us takes with him or her is the innermost self. If, in that moment of separation from the body you are unfamiliar with your true Self, the part of you who knows God, then you will naturally look to leaving this world with fear and attachment; this attachment is what compels you back into material existence again and again. Only when you have the balance to walk out of the doorway of this body without attachment are you truly free to explore the vast infinite reaches of Divine Consciousness without fetter or limit—you are then a jivanmukta, a truly free soul.

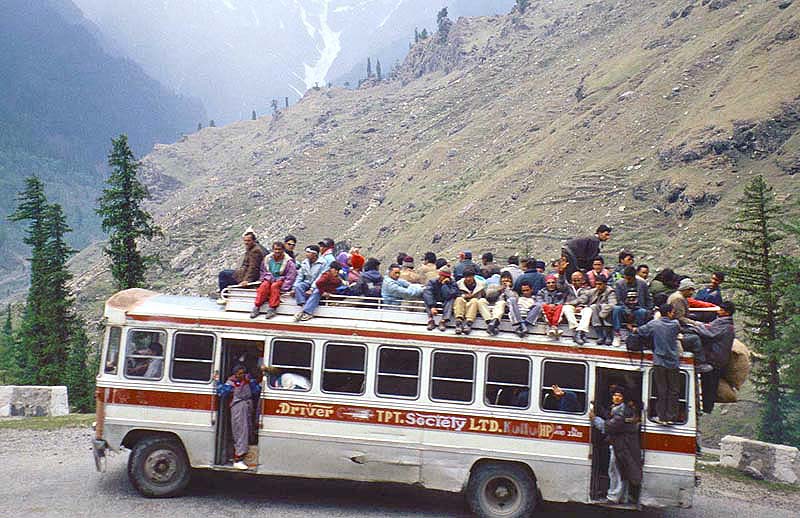

Picture: Bus on India’s Mountain Roads

Picture: Bus on India’s Mountain Roads