Originally appeared in The Cross and Lotus Journal; 2003 Vol. 4 No. 1 by John Durkin

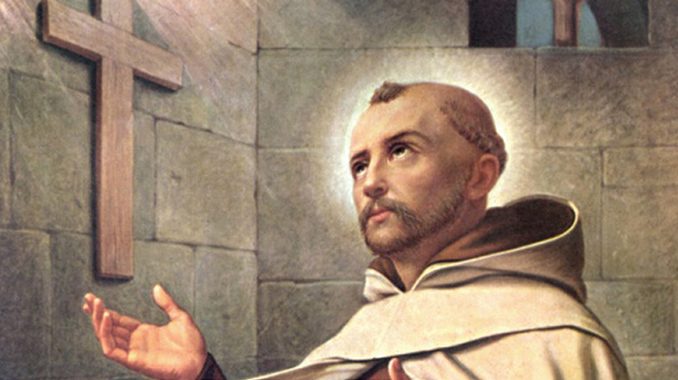

In the 1530’s in the Old Castile area of Spain the son of a wealthy silk merchant family, whose ancestors had been forced to convert to Christianity from Judaism, was traveling in his family business and fell in love with a beautiful weaver in one of the nearby towns. You know the rest, right out of Hollywood; God has been writing this stuff since the beginning of time. The woman probably was of Moorish heritage and the rich family could not accept her because accepting her into the family might open the whole issue of their own background. As a result the new family constantly was forced to live on the verge of starvation. They had three sons but the father and middle son would soon die as a result of malnutrition, overwork, and disease. Their youngest son, from Jewish and Moorish ancestors, was born on June 24th, 1542 and named Juan de Yepes y Alvarez. He was to become one of the most recognized mystics in the world, St. John of the Cross.

Through an incredible series of circumstances John graduated as a top student from one of the best universities in the world. He was ordained as a priest in 1567 and in that year met a dynamic nun who changed his whole life as he did hers. She was St. Teresa of Avila about 27 years older than John, and already involved in the reform of the Carmelite order. She convinced him to join her movement, resulting in an unfolding drama that engulfed both of them for the rest of their lives. They were completely different in temperament and approach to issues but were united in their commitment to union with Christ and reform of the Carmelite order.

The contradictions and drama that God built into John’s life in the beginning continued through his life and beyond his death. John wanted nothing more than to be a simple monk; God was having none of this however and filled almost all of his life with leadership and administrative /duties. John was seen by those in his care as a gentle and supportive man but was arrested by those who opposed him and subjected to physical and psychological abuse meant to curb his headstrong ways. While he was imprisoned he wrote the first 31 stanzas of a poem called The Spiritual Canticle as well as three shorter poems. Soon after he escaped from his captors, he completed other works including his most famous poem, “Dark Night.”

At the end of his life John was attacked by officials within his own reformed movement and stripped of all administrative duties. Attempts were made to discredit his position, to have him removed from the fold, and to accuse him of inappropriate behavior. While these maneuvers were going on John developed an infection and a sore on his foot; soon ulcers appeared on other parts of his body. On his deathbed John asked his fellow monks to read the Song of Songs (Canticle of Canticles) from the Bible. At midnight the bell of matins rang. John’s dry wit came through with, “I will say matins in heaven”; he died about midnight on December 14, 1591.

The surrounding population immediately swarmed the priory to receive the blessing of someone they knew to be a saint. They tore pieces from his clothes, his bandages, and even bits from his body. Even in death the introvert who preferred to meditate hidden in the outdoors became part of a huge public spectacle. The process of beatification started 20 years after his death, soon enough that even his older brother could testify as to the events of his life. He was beatified in 1675, canonized in 1725 and declared a Doctor or great teacher of the Catholic Church in 1926. Now you can type his name in any search engine and get thousands of “hits.”

God’s final twist is that St. John of the Cross, the man who loved everything and everyone and who wrote poems of such ecstasy and joy, has come to be associated with something kind of spooky and painful, the so called “Dark Night of the Soul.” Our spiritual Essence may travel through dark nights but is always Divine. Perhaps it is just another case of God’s hiding the truth in plain sight.

St. John recognized that God was involved in his life and maintained an attitude of equanimity despite apparent contradictions, difficulties and setbacks. God’s plan does not arise from, nor can it be understood by, the intellect. Still he must have been bemused by the directions his life took and would have been startled to find that God had arranged for his life and writings to become known throughout the world.

The “Dark Night” is one of St. John’s most famous poems.

One dark night,

Fired with love’s urgent longings

-Ah, the sheer grace!-

I went out unseen,

My house being now all stilled.

In darkness, and secure,

By the secret ladder, disguised,

-Ah, the sheer grace!-

In darkness and concealment,

My house being now all stilled;

On that glad night,

In secret, for no one saw me,

Nor did I look at anything,

With no other light or guide

Than the one that burned in my heart;

This guided me

More surely than the light of noon

To where He waited for me

-Him I knew so well-

In a place where no one else appeared.

O guiding night!

O night more lovely than the dawn!

O night that has united

The Lover with His beloved,

Transforming the beloved in her Lover.

Upon my flowering breast

Which I kept wholly for Him alone,

There He lay sleeping,

And I caressing Him

There in a breeze from the fanning cedars.

When the breeze blew from the turret

Parting His hair,

He wounded my neck

With His gentle hand,

Suspending all my senses.

I abandoned and forgot myself,

Laying my face on my Beloved;

All things ceased;

I went out from myself,

Leaving my cares

Forgotten among the lilies.

St. John used two books to comment on the first two stanzas of this poem so I will not attempt to explain it in a few lines. There are two nights referred to in the poem; each of these nights has active and passive aspects. The first stanza denotes the night of the senses where the spiritual aspirant gradually learns to control inordinate attachments in order to find what the heart really wants. Sometimes people get confused and think that austerities and control are the point, going even to the extreme of making it a kind of contest to see who can have the greatest control. The point is getting to a feeling of detachment from our desires without falling into the greater trap of adding the desire for no desires.

Sometimes St. John is presented incorrectly as a model of negation and deprivation. Mother Hamilton said that she tried the path of negation and abandoned it in favor of a path of seeing everything as God. At the same time she entreated us to keep our attention only on God. St. John saw the path of detachment not as negation but as a freeing of the soul from inappropriate energy loss, to use modern terminology, so we could keep our attention on God. Both Mother and Papa Ramdas entreated us again and again to abandon everything but the direct knowledge of our oneness with God.

The second stanza refers to the night of the spirit. In the active sense this night refers to making appropriate decisions that lead to more likelihood of union with God. During the passive night of the spirit God acts on us to prepare us for our union with the Bridegroom, with God acting on us may very well feel like we have been abandoned or are being punished. Indeed children may feel this way when parents leave them at school for the first day or make them act in particular ways. But the parents are demonstrating love and indeed also may be suffering when they see their children suffering. It still has to be done. Detachment from our own desires and acceptance of the reality of God’s grace and love are the necessary approaches to this second night.

The word “secret” in the poem needs a brief comment. “Secret” does not refer to some technique or path that some know but that is hidden from others. The secret is God’s secret and can not be learned by the intellect or guaranteed by some particular group of behaviors.

The final stanzas of the poem describe the joy and the ecstasy of union with the Divine. St. John used images, including bride and bridegroom, from the Song of Songs in the Bible as the basis for his poem. However, “Dark Night” carries its wonderful message even for those who have not read the Song of Songs.

In “Dark Night,” as in all of John’s poetry, the primacy of God’s love for us is the essential message. God’s reaching out to us leads to our union with the Divine, if we are receptive. We aid this process by controlling inappropriate desires and by accepting the reality of God’s great love even during times when we might feel abandoned. The message of St. John of the Cross reaches from sixteenth century Spain to join that of the great spiritual leaders from all backgrounds to show us the way to the continued joy and ecstasy of realizing our true nature.